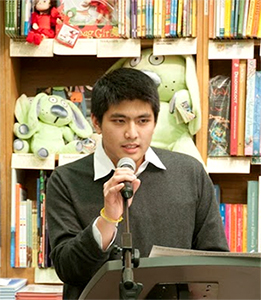

Jirayut “New” Latthivongskorn

On November 12, 2019, Jirayut (“New”) Latthivongskorn testified in Washington, D.C., at a U.S. Supreme Court hearing as one of the plaintiffs fighting the ending of Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, commonly known as DACA—a program that protects him and more than 660,000 undocumented young adults nationwide from deportation. Read the full story here.

New Latthivongskorn was born in Bangkok and lived there for nine years before coming to the United States with his family to escape poverty and find a better life. He is one of three siblings. For many years after arriving in America, New kept his undocumented status a secret. But as he came face-to-face with the injustice facing so many young immigrants in the United States, New began to speak out for change. Today, he is the first undocumented student in the medical school at the University of California, San Francisco.

Leaving the Middle Class, And Thailand

In Thailand, we had a nice house near the city center of Bangkok and my parents were business owners. My family had a huge work ethic, and I grew up in a financially comfortable household. My mom has seven siblings and, growing up, her mother worked long, tough days as a seamstress and doing odd jobs to support the family. But it was my aunt, my mother’s oldest sister, who led our family’s charge into the middle class—dropping out of high school to pay for her siblings’ education, and eventually starting a business, a tour company. The whole family got involved and later entered the real estate business. The family also had some involvement in construction companies. That’s the spirit of my family, we all worked together to make sure we all prospered together.

When the Thai economy crashed in the mid-1990s, New’s family came on hard times.

The family’s businesses weren’t profitable anymore. People weren’t traveling or buying houses, no one had money, and our family debts started to pile up. Everything was in jeopardy. For a few years, my parents tried to stick it out. They tried out different business ideas, but they got to the point where there was no way out. Later, I found out that my Mom was having suicidal thoughts around this time—she thought that if she ended her life right then, all of her obstacles would disappear. Luckily she didn’t follow through. Instead, she and my father made the decision to pursue a life in America. We had been in America before, two or three times, as tourists.

New’s parents traveled to Fremont, California, to stay with his aunt. They found work in Thai restaurants. The idea was that they would send for the children after they had settled in the United States. One of their main motivations in coming to America was to find a better future for their children. Getting a decent education in Thailand means going to expensive private schools. This was an impossibility for New and his siblings after the economy crashed.

Difficult New Beginnings

It was difficult to make a new start. My parents had been successful business people in Thailand, running their own businesses, and suddenly they were cleaning toilets, mopping floors. Managers would yell at them. And all of it was for my brother, my sister and myself. Coming here meant we could be part of America’s public education system. I still can’t believe how much my parents sacrificed to make sure we got a good education.

When we joined my parents, they didn’t tell us that we were moving here permanently. We thought we were going on another trip to visit family and have fun. After a few months, they sat us down and told us we were staying. I remember thinking—but what about my toys? Back in Thailand, I had these model robot kits that I loved. I also thought about all my third-grade friends I would never see again. I still had my little phone book with their numbers in it. My parents explained that we were going to be staying here without any visas or green cards. They wanted us to understand that this was what we had to do, that—as a family—this was our only option.

Keeping Our Family’s Undocumented Status a Secret

While New and his brother and sister were growing up in California, their parents told them not to talk to anyone about their immigration status. New entered into third grade and began to learn English. He says it was not until sixth grade that he was entirely comfortable carrying on a conversation with his American peers. At home, he and his family spoke a mix of Thai and English. His parents worked long hours from morning to night while New and his siblings were attending school.

My parents were often tired and stressed out, and I would ask them: “What can I do to help?” Without fail, they would say, “Just do your job, focus on your job.” That’s when I realized that education was my job. My job was to be successful, and I looked to education as my key to success. And so I set myself on that path and started working harder in school, and I began to excel. I believed that somewhere down the line it would all work out—that’s the American dream.

Fearing Deportation Throughout Teenage Years

New took honors and AP classes in high school and found himself settling into what he calls the “traditional teenage American experience.” He went to prom and participated in class trips and other school activities. Once he turned 16, however, he began to find that being undocumented in America was an enormous barrier to a successful and normal life. Always in the back of his mind was the fear that he and his family could be deported at any time.

My friends were starting to get drivers’ licenses and jobs, and people would ask me why I wasn’t doing those things. When are you going to get a car? When are you going to get a summer job? I would make jokes in response. “Oh, I’m afraid of driving,” I’d say. I said I would be a dangerous driver. These were the excuses I made.

I felt like I was just like all the other kids, but then there were these moments that would pop up and remind me I wasn’t. Even if I was hanging out at a park with friends and a police car or neighborhood security would drive by, I would feel a surge of fear. I would hold my breath. And it would remind me again, in a flash, that all the sacrifices my family had made could disappear in a moment.

I remember going with my friends to watch an R-rated movie and I didn’t have ID to prove my age so I couldn’t go in. It was embarrassing. I felt like I was just like all the other kids, but then there were these moments that would pop up and remind me I wasn’t. Even if I was hanging out at a park with friends and a police car or neighborhood security would drive by, I would feel a surge of fear. I would hold my breath. And it would remind me again, in a flash, that all the sacrifices my family had made could disappear in a moment.

As a family, we were very uninformed about immigration policies and very afraid of what it meant to be undocumented. There was always this looming risk of deportation. And we thought that we were somehow the only undocumented family around, so we didn’t tell anyone outside our family.

A Dream of Becoming a Doctor, and the Considerable Barriers to Getting There

Eventually, New’s family moved to Sacramento. His parents had been waiting tables for many years and decided to try their hand at opening their own restaurant so the family could have more money to send the children to college.

I worked at the restaurant on weekends and over the summers, sometimes even on weekdays when it was busy. I did everything. In between learning recipes, waiting tables, mopping floors, and washing dishes, I wrote my U.S. History papers in the back room when things weren’t too busy. I learned a lot, but most of all how, to become disciplined.

New had tried not to worry a great deal about what he wanted to do with his life after high school and, hopefully, college. His focus in those years was on getting good grades and supporting the family. During his junior year, New’s mother had to go to the hospital for a hysterectomy. While he was taking care of her in the hospital and watching all of the staff do their work, New decided he wanted to be a doctor. Specifically, he wanted to serve the medical needs of immigrant and low-income communities; to change the lack of access to health care his and other immigrant families face. It wasn’t long before New began to explore opportunities for college so he could pursue this aspiration. One considerable barrier in his way, however, was the lack of financial aid for undocumented students.

Missing Some Documentation

I always thought I’d be able to go to college. I guess I was naïve. I just hoped it would all somehow work out. We accepted that there would be no financial aid. My brother was already at a state school and he didn’t get financial aid.

New was accepted to four of the University of California (U.C.) schools. To his surprise, he also was offered a scholarship that would have covered most of his educational expenses for four years.

I was ecstatic knowing that I wouldn’t have to burden my parents to help pay for too much of college. But two weeks before the deadline to register, I got an email that said I was missing some documentation. I went in to talk to the people there and I told them that I didn’t have a Social Security number or a green card. They said, “We’re sorry, you can’t have the scholarship. Come back when your status changes.” This was the exact phrase they used: “Come back when your status changes.” It was only three months before college started and it was one of the biggest roadblocks I’d come up against. I was devastated.

New began considering a less expensive community college, but his family insisted that he should attend U.C. Berkeley and that they would figure out how to pay for it. He entered Berkeley as a freshman in 2008.

Starting College Life With The Question: How Are We Going to Pay for The Next Year?

The first year at Berkeley was an extension of the American dream I’d been living. I was still able to put off the reality of what it meant to be undocumented. I was going to classes, living in the dorms, and having that traditional experience. And then towards the end of my first year, the challenges started coming back again. The big question was how we were going to pay for the next year. And I realized this was not sustainable, we could not pay out-of-pocket for all four years.

In those moments of desperation and uncertainty, I pushed myself to search and apply far and wide for different private scholarships that might be open to undocumented students. I worked part-time as a busboy at a Thai restaurant near campus and eventually I did get a first scholarship through E4FC, Educators for Fair Consideration. They’re a nonprofit organization that supports immigrant students, undocumented students particularly.

I remember my parents were with me, my whole family, and we looked at each other and whispered, “Are all of these other people undocumented, too?” It was my first exposure to that community. That’s the moment when I starting coming to terms with my undocumented identity.

At the scholarship ceremony, I met other undocumented students for the first time. I remember my parents were with me, my whole family, and we looked at each other and whispered, “Are all of these other people undocumented, too?” It was my first exposure to that community. That’s the moment when I starting coming to terms with my undocumented identity.

Finding Community

Through E4FC, I met other undocumented students and we got together every week to write something about our immigration experience. It became like a therapy session. I ended up writing two short creative writing pieces that I performed at a commemorative event on Angel Island. There were 150 people in the audience. It was my first public experience, my first time “coming out” as being undocumented. It was scary and powerful at the same time. Everybody in that class shared parts of themselves, they were all vulnerable, and I got to see other people who had gone through similar experiences, who understood what I had gone through. My parents were nervous about my public appearance. In the booklet for the event, we decided to cut off part of our last name, to try to remain slightly anonymous. But my family got to hear other peoples’ stories and it was a great moment of growth for all of us.

As New was becoming more comfortable talking about his undocumented status, the federal DREAM Act was coming up for a vote in 2010. If passed, it would provide conditional permanent residency for undocumented immigrant youth that qualified under the criteria of having moved here before the age of 16, and currently being under the age of 30. There was not much time.

The Duty to Act on Behalf of Other Undocumented Youth

I was on the fence about how I was going to be involved in the movement, but there was a moment at Berkeley that changed my thinking completely. It was in my endocrinology class. There was a student strike that day protesting tuition hikes. We were encouraged to skip classes, but I went because I thought I shouldn’t miss even one day. And instead of covering the subject we were supposed to cover, my professor talked about himself, about his own journey in America. He had gone to prestigious Ivy League colleges and was often the only African American student in his classes. He talked about how he learned to speak up and be active. He told us he appreciated that we all came to class today, but he said we also needed to realize that we had a role to play in what was happening that day. I remember he put up an Einstein quote on the board: “Those who have the privilege to know have the duty to act.”

That was a light bulb moment for me. I realized I was privileged to be sitting there in this man’s class, but I didn’t get there by myself. My parents were still working hard to support me, my sister was in community college while working as a waitress to support herself and to help me. At that moment, I knew I had to do whatever I could to get the DREAM Act passed.

During finals that year, I was more stressed out about what I could do to push the DREAM Act than about my exams. With Asian Students Promoting Immigrant Rights through Education (ASPIRE), the first Asian & Pacific Islander undocumented immigrant youth organization, we held phone-banking parties and mobilized letters of support. When the vote fell short, just by a few votes, I grieved with my newfound community members of other undocumented immigrant youth, role models, mentors, and allies. Though I was sad, I knew I had done all that I could at the time.

Undocumented and Unafraid

In 2011, California lawmakers began considering a law (the California DREAM Act) that would make undocumented students at state universities eligible for financial aid, scholarships and other means of support available to other students. Each year, about 25,000 undocumented students graduate from high schools in the state. Undocumented immigrant students at Berkeley and other campuses were starting to speak out for the legislation. They were going public about their undocumented status and the challenges they faced.

I testified at the State Capitol in support of the California DREAM Act, lobbied and organized. And when it finally passed, I was just about to finish college. To my surprise, the California DREAM Act kicked in before my last semester at Berkeley. In combination with my private scholarships, I paid nothing. It all came full circle.

New continued his activism by getting involved in the push for the TRUST Act, a California measure that placed limits on deportations of undocumented immigrants arrested for or convicted of minor crimes. The TRUST Act passed in 2013.

Living a Parallel Life

While I was working to get the TRUST Act passed, I shared a personal story. I got mugged at gunpoint in Berkeley, right in front of my apartment, just five blocks from campus. Luckily, nothing happened to me, they just took my phone. I went home, told my roommates what happened, and then I sat down to study. I had five midterms the next two days, including a Japanese test and biochemistry exam that next day. One of my roommates asked, “Don’t you want to call the police?” The truth was that I did, but I was afraid that if I reported the crime something might happen and I could end up getting deported. I was afraid. Coincidentally, the police later arrested a suspect and I was asked to come identify him. When I got to the police station, it was the guy who’d robbed me. I’ve since learned that people in immigrant communities are often afraid of asking for support from police. It’s just another example of how immigrants really live in another world in this country.

“My Well-Being is Connected to My Community’s Well-Being.”

As New came to the end of his undergraduate years at Berkeley, he began to explore his options for medical school. He also joined with other students to form a group called Pre-Health Dreamers (PHD), with the goal of supporting undocumented students pursuing careers in health and science. Today, PHD has a network of 250 students across the United States. It provides resources, information, and mentorship in addition to advocating for institutional change to make graduate & health professional schools more welcoming of undocumented immigrant students.

New started medical school at the University of California, San Francisco in 2014. He is the university’s first undocumented medical student and is enrolled in PRIME-US, a program for students who specifically want to practice medicine in urban underserved communities.

When I finally started medical school , I made a commitment to follow my own aspirations and grow in new ways. I needed to keep myself accountable to something bigger, because my well-being is tied to my community’s well-being. I may not be able to be as active in the immigrant community while I am in medical school, but in a few years I’ll go back and be of even greater service, in a new, different, and—hopefully—more impactful way as a doctor that my community deserves.

New and the rest of his family have applied for permanent residency in the United States but later learned that there is no way to adjust their status without leaving the United States, which would trigger a 10-year bar from them returning to America. In the meantime, New has qualified for temporary work authorization and relief from deportation under President Obama’s Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program.

Related Content

- Listen to New’s KQED Perspective, Old Path to a New Destination (May 2014)

- Watch New’s interview on MSNBC as he share his immigration story and what he hopes to see in the future for immigration reform in this country. (December 2014)